- Small Wire

- Posts

- On beauty

On beauty

I went to see The House of Mirth, the movie, at a museum in Queens last weekend. The movie kept stopping because the projector would break, which also happened last time I went to see a movie there (Hurricane Season). I had underestimated how much The House of Mirth upsets me. I first read the book as a teenager and have had a visceral relationship to it ever since. I wrote a little bit about it already on this newsletter before and also have an essay coming out about it at some point soon in The Cleveland Review of Books. My emotions around The House of Mirth are compounded by the fact that I, like Lily Bart, am presently 29. My Lily Bart year, I like to call it. It feels like we are on the same doomed rollercoaster.

The House of Mirth, the movie, is more an interpretation than a translation of The House of Mirth, the book. It’s more romantic and melodramatic and lacks some of the blunt edges and viciousness of Wharton’s novel. Gillian Anderson, replete with red curls and frilly Edwardian gowns, is magnetic. She melts constantly into her love interest’s arms and then recoils. He holds her dead hand at the end and weeps, framed like a painting. In her tableau vivant, one of the infamous scenes from the book where Lily dresses up in a scandalously revealing dress posing as “Mrs. Richard Bennett Lloyd” and elicits crude comments from the men watching, Gillian Anderson dresses up instead as Watteau’s “Summer.” No one really seems to be watching.

I wonder if part of what is difficult about the adaptation is how much the book centers around Lily’s being beautiful. She is naturally beautiful and also artificially beautiful, going deeply into debt to her dressmaker and milliner to stay primped up in the fashions of the day. All anyone can talk about is how beautiful she is. What I find interesting about The House of Mirth is how Wharton shows not just how beauty can set you apart, but also how it obscures interiority, closes off outcomes. Lily is reduced to being beautiful. But the book is largely told from her perspective. We come to understand that she has thoughts and feelings and desires. On screen, simply presented with beauty, we become like Lily’s peers. After all, all we know how to do with beauty is consume it.

In My Life as a Godard Movie, the critic Joanna Walsh rewatches Godard movies and wonders about beauty. The women in Godard movies are always very beautiful. Godard supposedly advertised for a “girlfriend/muse” and got Anna Karina, the most beautiful of them all. Karina, like Marilyn Monroe, is perhaps more beautiful in action than she is in still photographs. She has presence, charm, an aura. She is less conscious, maybe, of being watched than she is when posing. “Can a woman’s beauty be privatised?” wonders Walsh. “Once shot, you can sell it, lend it, rent it. The more she shows her beauty, the more its value increases: value that she contained, detaches from her background. You can no longer hold on to the beauty you have made together, which would not exist without the camera.”

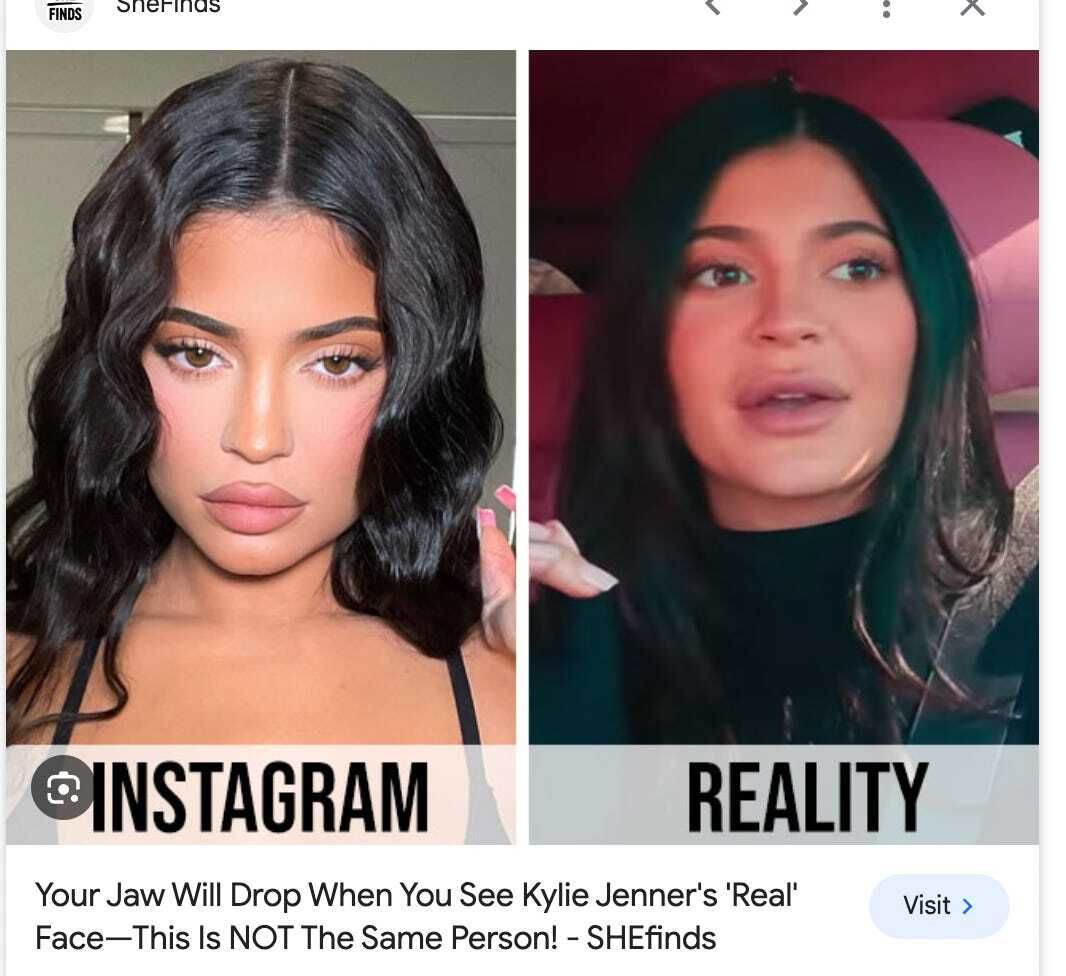

Before camera, before movies, the only way to hold a woman’s beauty captive was to hold the woman captive. In an era of endless images, when we can look at ourselves all the time and look at other women all the time, all day long, an endless stream of women, beauty becomes a different kind of signifier, diffuse, disembodied. So many photographs that are disseminated are massively altered. Celebrities appear photoshopped within an inch of their lives, their skin poreless, their waists shrunken, their skin lightened or darkened variously. And although there are usually real life photos of them you can put side by side, as many Instagram fan accounts do, and say reasonably that they do not resemble these doll like figures, that also seems like an obsessive and petty exercise. Who cares, after all, if a famous woman or her PR representative edits her photos? Who cares even if a girl you follow online, who is likely not very famous, edits her photos?

There is something about giving over your own image to digital modification that feels strange, an uncanny valley. I have never significantly modified a photo of me (I have, like most people who publicly publish photos of themselves, erased acne and wrinkles and creases and folds). Once, I downloaded Face App, an AI platform that uses neural networks to transform photos. I plugged in a picture where I was frowning. The smile that was produced was bland, placid, almost monstrous. It did not look like me. It looked like someone’s composite idea of a girl. When you do significant photo editing of this kind or when you generate AI photos of women, what it generally looks like is if you took the common markers of beauty or womanhood off a body (a smile, breasts, thick hair, waxy skin, big anime child eyes) and put them together in a sort of loose assemblage. It is the barest signifier of a woman.

AI porn, which has become ubiquitous across the internet, and its counterpart, real porn edited all the way to the point of irreality, emphasize this kind of dehumanization. Beauty is nothing. A body is nothing. It is like a really lustful god got bored halfway through his creation and left half his people half-formed, no more than a suggestion. I am fairly neutral about porn in general, which does not seem to be the worst form of objectification to me. But being attracted to AI porn or to very obviously digitally modified photographs that do not look like a person feels eerie to me. It seems evidence of such a discomfort with or disinterest in the idea of beauty that is sentient, that can desire or participate or resist, that it must be flattened into a sheer product. It is the ultimate form of commodification. The image of a person that is literally no more than a commodity.

It was a very warm day when I went to see The House of Mirth, the first very warm day this year in New York. I was dressed up in my dolly clothes, a very short lace and linen dress, clunky heels, a pink bag, all my whimsy jewelry. It made me feel worse after the movie, in my spiral of self-doubt about being 29, about being frivolous, being in debt, being so subsumed, so slavishly devoted to this dull and generic form of femininity that I cannot get out from under it, about sometimes glancingly, startlingly finding myself beautiful, and then being shocked back to sobriety. I’m not all that.

In The House of Mirth, as in life, beauty is never just beauty. It is wealth, it is a currency, it is thingified, auctioned off, made ornamental. Lily, relatably, is desperate to be desired by everyone and then is disgusted by the kind of desire she receives. It alienates her from herself because it is possessive and obtrusive and oblivious to her personhood.

People who are really obsessed with beauty, who want to possess it or to inhabit it, are also really obsessed in my experience with the experiential of being beautiful, with what it feels like to be visible in that particular way. On the internet, lonely, virulently misogynist men, often speculate about the interiority of conventionally attractive women and about how they must feel. They long, I assume, to be intensely desired, despite the paradigm of heterosexuality which dictates that men must desire and pursue and that women must passively receive desire. The National Review and The Spectator this week both published wildly fantastical and bizarre defenses of Sydney Sweeney and how she was ushering in a new era of “busty blondes.” Sweeney, who infamously threw her mother a MAGA-themed birthday party and who has no apparent acting talent, is obviously touted here as a symbol of a new Aryan ideal. Tussling over whether she is unusually beautiful or not seems like like a zero sum game. If she is undoubtedly considered exceptionally attractive because she belongs to a society that excessively valorizes her particular markers of beauty, trying to categorize anyone’s level of beauty feels like a trap. At some point, you will always end up with a hierarchy.

But there is no scarcity of beauty. Beauty is infinite. An infinite number of people can be beautiful, all in different ways. This sounds like hippie jargon, but to try and put a cap on beauty is precisely to make it into a currency, to commodify it. Attached to people’s bodies, beauty ages, it morphs, it transforms, it depends on the gaze of the beholder. Displaced from people’s bodies and reified into something totally separate, it becomes static. A thing that can be frozen in time.

Reply